If Parenthood isn’t an atypical television product readily consumed by neurodiverse youth (see previously post), then The Big Bang Theory is. The combination of four socially awkward college-aged lads bonded together in geekdom, the use of visual humour, high-brow science-related material throughout the script and the academic setting of Caltech appeals to many neurodiverse youth. And when cameos… Continue reading Time to say goodbye to Sheldon?

Maxed Out

Neurodiverse representations in pop culture abound today, albeit mostly in male characters (the lack of neurodiverse females in pop culture to be addressed in another post). The US produced TV series Parenthood (2010 -2015) and the characterization of Asperger’s Syndrome in Max Braverman, gave audiences an in-depth look at neurodiversity in a familial setting and… Continue reading Maxed Out

Social Media: The Ultimate Level Playing Field

Neurotypical youth and their engagement with social media and other digital communication tools, is the subject of some consternation. Many are describing a dehumanization of youth (“zombieism”) through their constant attachment to digital devices and a radical move away from using traditional channels of communication (Boyd, 2008). Conversely, neurodiverse youth are experiencing social media platforms… Continue reading Social Media: The Ultimate Level Playing Field

Mitigated Echolalia and Popular Texts: The untapped resource for teaching curriculum to neurodiverse students

The Diagnostic Statistical Manual 5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) cites people with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as exhibiting restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities. In the case of stereotyped repetitive speech and ritualized verbal patterns, some behavior can be referred to as echolalia. Echolalia simply means repeating words that aren’t yours (literally ‘echo’… Continue reading Mitigated Echolalia and Popular Texts: The untapped resource for teaching curriculum to neurodiverse students

On the road from Autism awareness to neurodiversity acceptance (Part B)

And the problem is, people meet me and they go, “well what’s wrong with you?” And I go, “well, there’s nothing wrong with me”. “I thought you’d got Aspergers?” And they always think of Rain Man. “Oh you’re not like Rain Man, and I go “Why should I be like bloody Rain Man?! “Because it’s just a stereotype. –… Continue reading On the road from Autism awareness to neurodiversity acceptance (Part B)

On the road from Autism awareness to neurodiversity acceptance (Part A)

Acceptance speeches, particularly those given at the esteemed Academy Awards (or ‘Oscars’), are their own unique form of popular text. These 45 second monologues (that’s the official length although as we know they can vary tremendously) are a glossy, contrived and heavily produced mix of images and sounds that help feed the self-inflated over importance the Hollywood film industry assumes in global news and significance. One could argue that these monologues are also the tangible pinnacle of a winning actor or actress’ career.

Oscars acceptance speeches have a level a high degree of permanence. Mass media outlets are almost guaranteed to include a grab or sound bite from any of The Big Five Oscar Awards winners as part of their Academy Awards broadcast package, they live forever on video platforms like YouTube and become re-edited into subsequent Oscar broadcasts. These speeches also have the ability to become soapbox platforms where the personal opinions of winners become heard by millions around the world in an effort to garner awareness of certain sociopolitical issues. Take for example Marlon Brando’s 1973 (non)acceptance speech, given in proxy by Sacheen Littlefeather in support of Native American rights, Michael Moore’s 2003 statements on the US President and Patricia Arquette’s call pay equality for women in the USA.

Autism Awareness

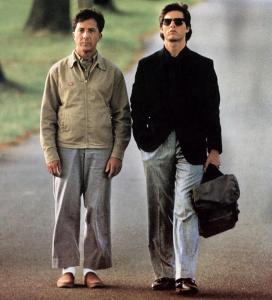

The feature length film Rain Man (1988) placed the neurological condition ‘autism’ onto the mental landscapes of millions around the world. Widely recognized as the first filmic depiction of articulated autism, Rain Man showed the personal and social issues of autism, and society’s inability to handle both. With its paltry budget of $25million, the film reaped over $350million globally – not shabby for a ‘people film’ in the era of sci-fi and action blockbusters. Interestingly women flocked to see this film, with over 55% of the audience comprising female patrons. That’s significant for a buddy film/road movie with no female leads or strong romantic storyline. Were theatres full of mothers of autistic children drawn to the film, or just female fans of heartthrob support actor Tom Cruise? I don’t think we’ll know the answer to that, but it does bear mention.

Cruise’s portrayal of neurotypical Charlie Babbitt embodied the public’s historic ignorance, disrespect and confusion when interacting with neurodiverse people. The storyline oscillated between pity, manipulation and the institutionalization of Charlie’s autistic savant brother Raymond (the ‘Rain Man’): those societal attitudes towards autism that modern proponents of neurodiversity challenge. But in 1989, these aspects were overlooked and the feel good factor of two diametrically different brothers finding each other, and themselves in the process, won Rain Man Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Actor for Dustin Hoffman for his portrayal of Raymond Babbitt. The movie, by all measurables, was a huge success.

An acceptance speech that furthered non-acceptance?

Hoffman’s announcement as Best Actor was met with rapturous applause and a longer than usual standing ovation from his peers in the room that night; an indication that he had done a stellar job portraying the unique role of Raymond Babbitt. Such was the adulation from the crowd that whatever words were about to pour out of Hoffman would be pivotal in cementing public attitudes towards autism – after all he was the hero that had portrayed an autistic man on the big screen.

In his tender and reflective speech Hoffman thanked members of the autistic community and their families, the doctors and nurses who had helped advise him on his role, and referred throughout to “disability”. He did not celebrate the neurodiverse individuals he met but instead thanked the counsel of neurotypicals for the role. Unwittingly, and in one fell swoop, Hoffman created a ‘them and us’ attitude towards people with autism, medicalised the condition and positioned autism in the realm of the disabled. But the opportunity to champion autistic rights and celebrate neurodiversity – the subconscious issues at the heart of the movie he had just starred in – was missed. Hoffman hasn’t shied away from using an Oscar’s acceptance speech to make a sociopolitical point, with his 1980 rant against the very Academy Awards as a case in point. But on that night, Hoffman was happy to play into the audience’s adulation for somehow getting into the minds and deciphering a code about this group of people that no one before had managed on the big screen.

Much has been written on Hoffman’s preparation for the role where he befriended two real life people, one savant Kim Peek and one autistic John Sullivan, and meshed both their traits into Raymond Babbitt. The outcome is a representation of every stereotypical autistic characteristic imaginable: lack of eye contact, echolalia, propensity to think only literally and difficulties with abstraction, sensory processing issues and autistic breakdowns. He then coupled these with savant abilities: pattern thinking, ability to calculate complex mathematical calculations, memory for dates, and an advanced ability to remember facts to create Raymond Babbitt. It was these savant characteristics that became the qualities that endeared Raymond to his estranged brother in the film and stuck with audiences as defining ‘autism’. Essentially Rain Man incorrectly became known as a film about autism, NOT a film about savantism: it raised awareness and curiosity about autism but was simultaneously roundly criticised for inaccurately portraying the neurology. And for neurodiverse youth, Rain Man had become another obstacle to overcome in their pursuit of individual identity.